Cost Analysis: Are you Making Money?

How do you know if you’re making money? And what can you do if you’re not? Most small processors (like most small businesses) don’t fully understand why they are or aren’t making money and what they can do about it.

Here, Arion Thiboumery, co-founder of the Niche Meat Processor Assistance Network and a processor himself (Lorentz Meats, Vermont Packinghouse), introduces systems to help you sort out which activities in your plant are most profitable and which are less profitable. Armed with this financial information, you can make decisions that improve your business’s performance.

This page is based on a NMPAN webinar Arion gave on this subject on March 19, 2014. Watch the full webinar (1 hour) here: “Cost Analysis: Are You Making Money?”

How do you know if you’re making money?

Here’s what we often hear from small meat processors:

- ‘I check my bank account balance every week.’

- ‘I ask my accountant.’

- ‘We’re in the black at the end of the year.’

- ‘I work like hell to get as much done as possible.’

Is there a better way? How can you tell which activities within your plant are profitable, and which are not? To do this, we need organized ways to collect information.

We assume you want your business to make money: this isn’t a hobby. There are two ways to make money:

- Do things that are profitable.

- Stop doing things that are NOT profitable.

We all have pet projects we really like but may not be profitable. Sometimes we need them for the rest of our business. For example, you may make a certain value-added product that isn’t very profitable in order to gain business that IS more profitable. That’s OK: what matters if that you actually know which activities are profitable and which aren’t, and you aren’t just guessing or hoping they all make you money.

To figure out which activities are profitable and which aren’t, we need to look at what happens in our plant on a daily basis. We’ll start with a 30,000 foot view, then zoom in on daily in-plant activities and goals.

Using Departments: From One Cup to Three Cups

At many small packing plants, taking that big picture view, we have three main activities:

- Processing (which includes slaughter and fabrication)

- Further processing (grinding, sausage making, etc.)

- Retail

Those three main activities become our “departments.” Tracking income and expenses by department is a method of cost accounting, supported by GAAP: Generally Accepted Accounting Principles.

Think of it like this: imagine that your bank account is a cup, like a coffee cup. All your money, all your revenue goes into that cup and all your expenses come out of that one cup.

Farmer Jones drops off a steer for processing: she wants it slaughtered, cut and wrapped, and the ground beef made into 1 lb. packages. All the money that Farmer Jones pays for those activities — slaughter, fabrication, grinding, packaging — goes into that one cup. All the expenses come out of that same cup: you pay the people who work on the kill floor, in the cutting room, in packaging. You buy butcher paper and supplies, and so on.

If you only have one cup, it is very difficult to tell which activities are making money and which are losing money. If an employee on the kill floor is really slow and you are actually losing money there, you won’t be able to tell.

A better technique is to break down your organization into multiple cups, by department. So, now you have three cups: one for processing, one for further processing and one for retail.

All the revenue and all the expenses associated with slaughter and fabrication go into the processing cup. You make that department its own stand-alone business within your company. This system gives you a better sense of what is going on.

For example, all the revenue associated with further processing is in the further processing cup, or department, and so are all the expenses like seasonings, casings, labor and so on. At the end of the month, you might see that that department has a negative balance and is losing money. That is a clue that you are not charging enough for sausage making.

Before, when everything went into one cup, the other, more profitable departments were carrying the weight of the less profitable departments, and you couldn’t tell which activities were making money and which were not.

Setting Production Goals

Now that we have individual departments, we can set production goals. Production goals are the amount of work that needs to be done to make sure each department is profitable. We first need some basic information to set our production goals:

- Cost of goods (COG): the labor and materials (packaging, spices, and so on) that goes into that department. For the processing department, COG includes kill floor labor, cutting room labor, and supplies like butcher paper and Cryovac bags.

- Overhead allocated to this department: a percentage of our total overhead (we’ll discuss below how to determine your overhead and percentage allocations).

- Price of the product: this is what we charge our customer, e.g., $0.50/lb. on the hanging weight for cut & wrap.

To set production goals that are profitable for our plant, we need our cost of goods plus overhead to be less than the revenue (cut & wrap price multiplied by pounds processed) we receive from the customer.

For example, if our daily COG + Overhead = $1,000 for the processing department, we need to make at least $1,000 in revenue from that department today.

How do we do that? At $0.50/lb., we need to process at least 2,000 carcass lbs. Or about 3 to 4 beef, depending on carcass size.

We now have a very clear production goal for the day: process three beef. We didn’t have to look at our P&L statement or ask our accountant if we made money today. We can just ask the guys in the cutting room: did we meet our production goal? Did we cut 3 or more beef today?

What About Overhead?

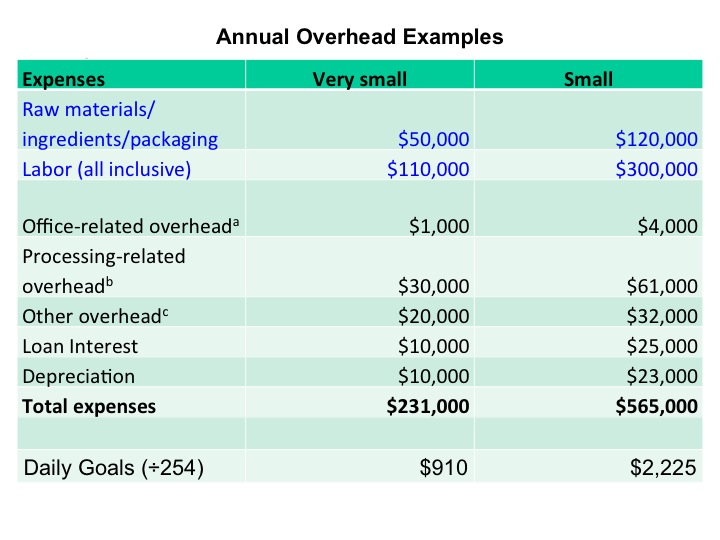

Overhead is all the other expenses — above and beyond your Cost of Goods — it takes to run a small processing plant. To calculate daily overhead, add up all of these expenses and divide the total by 254 (the standard number of work days in a calendar year).

Then, once you have a daily overhead number, allocate it by department by putting a certain percentage of overhead in each individual cup. Sometimes people are unsure how to do this. One of the best methods is to allocate overhead by labor-hours:

- Say you have 5 employees and each works 40 hours per week.

- Four of them work in the cutting room and one makes sausage.

- That means every week 4/5ths (or 80%) of your labor hours occur in the cutting room: allocate 80% of your overhead to that department.

This method is the most effective because it tells you where in your plant activity is occurring.

Common Concerns When Determining Overhead

“But my employees work all over the place!”

That’s very common in small plants, where employees take on a variety of tasks. In this case, allocate their wages to individual departments on an approximate percentage basis. For example:

- Fred works about half his time on the kill floor and half in the cutting room.

- Allocate 50% of Fred’s labor cost to the slaughter department and 50% to the processing department.

Don’t worry about being super-precise: just estimate on a yearly basis. And don’t divide Fred into smaller increments than about 20 or 25%.

“But we can’t cut that much in a day!”

What if you set your production goal and then think, “we can’t cut that much in a day, it’s just not possible”? Your production goals are based on meeting expenses: if you aren’t meeting your daily production goals, you need to find a way to get there. Either raise prices, add more staff or try to get the work done faster.

Production incentives can be really helpful here. You can reward your employees for meeting production goals: “Each day that we meet this goal, everyone gets their hourly wage plus an extra $X.”

“Why would hourly employees work faster?”

If you’re concerned that hourly employees will have a disincentive to work faster because they’ll be paid less, you can offer a minimum hour guarantee. For example if your work day ends at 4pm, say “if we meet our production goal before 4pm, I’ll still pay you for the full day and you can go home early.”

Think of it this way: you are billing your customers based on the amount of work done (you charge per pound on cut & wrap, not by how many hours it took you to fabricate the carcass), so why not pay your employees based on the same system? It really builds morale.

Sample Production Goals

Here are some examples of production goals from a small and very small plant.

Let’s start with the very small plant. Our production goal for the day is 4 beef. Let’s break that down even further and set the production goals to coincide with break time. Our day starts at 7am and the first break is at 9am. To stay on track, we should have one beef done by 9am. This makes it really clear for your employees what the goals are for the day: as you are coming up on the 9am break you can check in and see if they are close to being done with the first beef. Post these production goals right up on the wall in the cutting room so everyone can see them.

Very Small Plant — 4 custom beef, 5 people

- 9am — 1 beef

- 11am — 2 beef

- 2pm — 3 beef

- 4pm — 4 beef (done)

Here’s a small plant example — 27 beef, 14 people

- 9am — 8 beef done

- 11am — 15 beef done

- 1:30pm — 23 beef done

- 3:10 — 27 beef (done)

Sausage

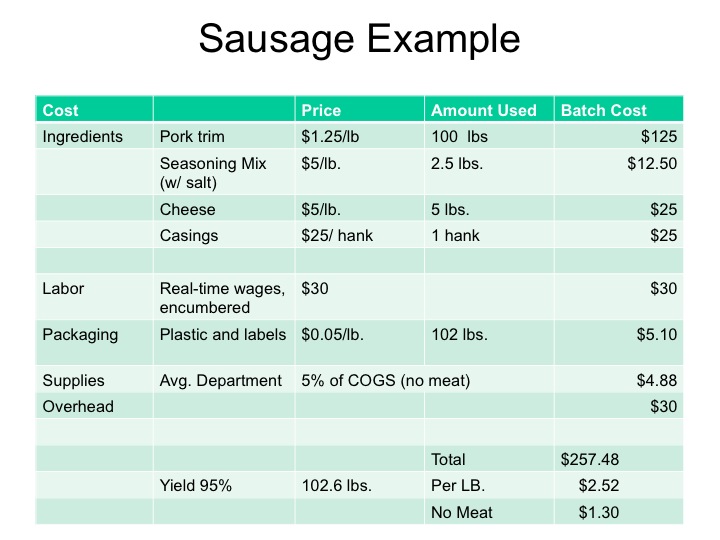

For sausage, you need the same information, but with a different angle. With products like sausage, we solve for price instead of weight to find our production goal. What you need to know:

- Cost of Goods = Labor + packaging (+ spices, etc.) — what does it take to produce a batch?

- Amount of overhead allocated to sausage area

- Batch weight and time to get a batch done (relative to goals)

Your equation: Weight x Price = COG + Overhead.

Enter weight, COG, and Overhead, and solve for price.

This table helps us calculate our cost of goods: we’ve got our ingredients and the amount of each ingredient we need per batch. We’ve got our labor costs: remember to use your “encumbered” wage. If you pay someone $10 per hour, it really costs you more like $12 or $13 per hour by the time you pay workers compensation, your share of FICA, and so on. So be sure and include your real cost, not just the hourly wage the employee is earning. The table also includes packaging and supplies as well as the overhead allocated to this department.

Notice that yield is also included: be sure and include that since we never get 100% on a processed product (unless you are adding a lot of water).

So, this batch of sausage costs us $2.52/lb. to make.

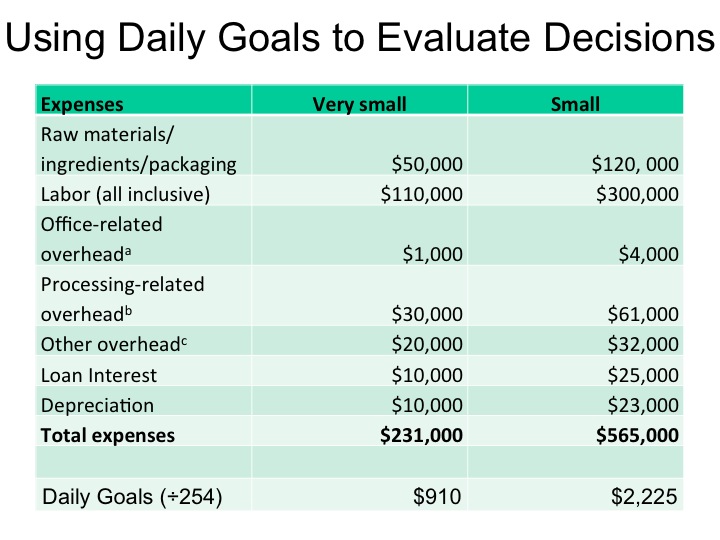

Using Daily Production Goals to Evaluate Decisions

We can also use our daily production goals to evaluate decisions. For example, to decide if buying a new piece of equipment is a good idea.

Let’s say you want to buy a new $50,000 sausage stuffer. Here’s the thought process:

- You are going to borrow the money to buy the stuffer and pay it back over 10 years.

- Now, that $50,000 stuffer plus interest costs $60,000. Spread out over 10 years = $6,000/yr.

- You have 254 production days in a year, so that stuffer costs $6,000/yr. divided by 254 = $24/day.

- So, you need to earn an additional $24/day in profit (profit = revenue less expenses) to justify buying the stuffer.

If you feel you can easily sell that much more sausage (or make that much more sausage for your processing customers), then buying the new stuffer becomes a pretty easy decision. It is a lot easier to look at $24 a day and think “can I make that much more money?” than to look at a $60,000 price tag and think “is it worth it?”

Now, we’ve covered a lot of ground here, on some complicated topics… at the end of the webinar, there was time for Q&A. If you have questions after reading through the information here, email us at nmpan@oregonstate.edu and we’ll try to get some answers for you.