Updated 3.29.2018

The Island Grown Farmer Cooperative (IGFC) mobile processing unit (MPU) was the first USDA-inspected mobile slaughter facility for red meat in the U.S. Further processing is done at a permanent plant in Bow, WA, also USDA-inspected.

Basic information

Capacity per day: MPU: about 9-10 head beef (or 35lamb or 15 pigs). This takes 2 butchers 8 hours, plus 2 hours drive time. The MPU can do this only 4 days/week, because of limited staff and the need to bring meat back to the processing plant and do truck/trailer cleaning/maintenance.

Hours/day of operation: up to 8 under inspection, extra for set-up & clean-up.

Weeks/year: 52, at 3-4 days/week. The processing plant operates 5 days/wk and can process 2500 lbs per day.

Species: all four legs

Services: slaughter & process; raw sausage; case-ready, retail packaging

Square feet: trailer is 34’ long. Plant is 3000 sf.

#/type of employees: 6 employees (from manager to part-time cleaning staff)

Annual sales revenues: $500,000 (all services, not including the value of meat processed).

Price of services: Slaughter: $40 lamb or goat, $55 pig, $105 steer. In order to have the unit come to their farm, producers have to have a minimum slaughter amount of $450. Cutting (to case ready) = $1.05/lb lamb, $0.82/lb steer, $0.6071 pig (plus 10% price increase, spring ’08). Sausage = $1.25/lb for links. (For farmers not in the co-op, prices are slightly higher.)

Operational costs: ~$294,500/yr. Fee structure is designed to break even or be slightly profitable. The trailer gets ~10 miles/gallon.

Retail on-site: Yes, small, selling co-op members’ meat (members get revenue). Open 2 days/wk, earns $9000/mo.

Wholesale: no

Inspection: USDA inspected

Certified organic: Yes

Certification agency: Washington Dept of Agriculture

Custom work: Yes but rarely, because too busy with inspected work.

Source verification on label: No, too much hassle. Appropriate when customers can’t meet producers directly. Some members have their own labels.

The market opportunity

“No one had a chance to try marketing before we had the processing – and now it’s taking off.”

Basic history/development

In 1996, a group of livestock farmers in San Juan County, Washington state, started talking with each other and the county extension service about how to make local meat production possible. The farmers lacked access to USDA slaughter and processing – they couldn’t transport their animals to facilities on the mainland. When the idea of a mobile slaughter unit came up, the farmers and the county extension agent approached the Lopez Community Land Trust, a community land trust focused on affordable housing and sustainable rural development, to be the host organization for the project. LCLT hired Bruce Dunlop to design and build the MPU.

The MPU is operated by the Island Grown Farmers Cooperative. The Co-op purchased it from LCLT, which is no longer actively involved in the business. IGFC formed specifically for this purpose of managing the mobile unit. It is a service co-op and does not have its own brand. There is a small retail operation at the fixed facility that is open two days per week, but most members market their products separately. In 2011, co-op membership reached 65 members. The general manager estimates that 95% of the co-op’s members use the co-op at least once a year and most use it more than once per year.The IGFC board, which meets monthly, makes all the basic business decisions. The head butcher now manages the MPU and the plant. Co-op member farms are all within 100 miles of each other (1-2 hours drive), which is the largest area the MPU can serve efficiently.

The MPU received its grant of inspection and began operating in 2002.

The Wall Street Journal published a story about creation of this mobile processing unit on October 6th, 2008. The article includes several photos and a video.

Funding sources

The total cost for the project was $150,000 in 2000. A new trailer in 2008 with the same capacity costs $170,000.

Trailer $60,000

Equipment & Installation $27,000

Truck $18,000

Design/ Project Mgmt. $25,000

Testing $15,000

Outreach $ 5,000

The MPU was paid for with grants, and private donations from the farmers and other individuals in the community, so neither IGFC nor LCLT had to take on initial debt. However, their experience suggests that an MPU could pay for itself, even with a loan to pay back.

USDA grants (obtained by LCLT), were from CREES (Cooperative Research Education and Extension Service), Rural Development, and Rural Business Opportunity programs, and paid for design, development, project management, and testing. A $20,000 grant from the Forest Service Community Development Program, for timber-impacted communities, paid for the truck and refrigeration equipment. The remaining $80-90,000 came from private, individual donors who wanted to support local agriculture.

Once the MPU was built, they didn’t need additional outside funding. They bootstrapped, with revenues (fee for service) and an initial capital charge of $600 from each of the 30 starting members. They set their rates so that they were able to break even in the first year.

The cut and wrap facility is on the mainland, in Bow. IGFC rents the building but owns much of the equipment, purchased from the landlord (assessed members an equity retain on each slaughter and paid it off in 4 years).

No bank financing as yet. To expand operations, they considered a bank loan. But members chose to loan IGFC the money themselves, at a slightly lower interest rate. This meant less paperwork – and a real vote of confidence in IGFC and the MPU.

Business plan

The initial business and operating plans were written by Bruce Dunlop for LCLT, before the cooperative was formed. As the business has changed and evolved, subsequent planning has been done by IGFC board members with business experience. The actual business turned out somewhat differently (Business planning for product sales is done at the member level, not by the co-op.)

Because they didn’t have to service any debt from MPU construction, business planning was fairly simple: estimate how many animals they’d handle and set appropriate rates. Members had to decide how much to charge themselves. (The MPU is available to non-members, depending on schedule, but at slightly higher rates.) Their original rates, based on an industry standard, were too low: after six months, they were losing money, so they raised rates. They’ve had to do so a couple of times since; a 10% hike in spring 2008 will cover rising fuel costs and health insurance/raises for employees.

“We took a big risk. The whole thing was built on faith that the animals would come.” Would they have enough business? “If you have enough capital, you can lose money in the first year. We had to break even because we didn’t have money to lose.” The gamble paid off: the MPU broke even in the first year.

Central to their success is this fact: none of these farmers has any other options for slaughter/processing, so they have to make this one work and keep it afloat.

Deciphering regulations and complying

The MPU is USDA inspected. To understand the USDA regulations, two IGFC members took a HACCP class (required). They wrote their first plan, based on the generic HACCP plan and guidelines on the USDA website. This was in 2001, when HACCP was first applied to small plants. They reviewed it with their HACCP class trainer and then presented it to USDA.

The HACCP plan and operating procedures are separate documents. You have to be careful about what goes in which. IGFC has adjusted this over the years, with guidance from their USDA inspectors. USDA requires specific “Sanitation Standard Operating Procedures” (SSOPs), including pest control and water supply testing. For the most part, USDA requires you to have a plan and follow it.

The HACCP coordinator is a critical job. HACCP is, in theory, straightforward. In practice, every inspector has his own interpretation. The coordinator must be able to work with the inspectors to craft the plan and then change it when it makes sense and to comply with changes in the regulations. The USDA can’t tell a processor how to write the plan. However, inspectors often have helpful recommendations. In IGFC’s experience, most inspectors are reasonable and willing to work with a processor to create a good, workable plan.

Apart from USDA regulatory requirements, IGFC’s processing operations required no other permits. The cut and wrap facility in Bow already had a conditional use permit for meat cutting. (A new or expanded facility would require a building permit.)

The MPU required no county permits, because it isn’t a building, so the county had no jurisdiction. Rinse water and offal are composted on-farm, but the amounts are small, and the county health department hasn’t objected. The MPU may visit each farm ten times a year, using 300 gallons each time: 3000 gallons per year is minimal for land application. As for offal, there are plenty of studies showing on-farm composting is safe (see, e.g. Washington State Department of Ecology guidelines: http://www.ecy.wa.gov/biblio/0507034.html).

Plant design

Bruce worked with Featherlite, a trailer company, to design the MPU. This was the first USDA-inspected mobile slaughter facility, so they had to start from scratch.

The photo on the left shows the MPU skinning and evisceration area as seen from rear of trailer. The photo on the right shows the carcass cooler behind the skinning area. Inedible offal and blood from livestock are composted at the respective farms.

Big Glitches and how they were solved

Operations have been relatively smooth from the beginning.

Required equipment

The unit is equipped with a diesel generator, water storage, hot water heater, refrigeration and tools to allow for fully self-contained operation. Carcasses begin chilling immediately after processing and are down to temperature by the next morning.

Staff needed and how they were found/trained, what they cost

There are currently six full-time staff:

• Two butchers who do slaughter and fabrication; they go out with the trailer, separately or together;

• Three additional meat cutters;

• Scheduler/packager who also answers phones.

They have part-time staff for clean-up and packaging.

Hourly rates run from $11.00/hr to about $22.00, depending on experience. A reasonably skilled meat cutter earns $18-19/hour.

The senior butcher, who is also now the plant manager, is a year-round employee, on salary. All others are on an hourly wage. In 2008, IGFC began offering health insurance and paid vacations to all full-time employees; the insurance, though quite expensive, was necessary to retain them. Labor amounts to 75% of total costs.

IGFC found their staff by doing “a lot of looking.” At the very start, they hired the senior butcher, who was then working at a custom butcher shop. He was very experienced: grew up in a butchering family and went to school for it in Holland.

They needed more help when they opened the Bow fabrication plant. They were fortunate to find, through word of mouth, another butcher with experience. They trained two additional meat cutters and their packager from scratch. They trained their third meat cutter, who started as a cleaner for the summer, through a state job retraining program that paid half his wages for 6 months.

Training didn’t always work. To be good at cutting meat takes two years on the job. Meat-cutting training programs are typically only for 5-6 months.

As is typical for the meat processing industry, seasonality is still a problem. Business is slow February through April, so they encourage employees to take unpaid vacations during that time. It works out for everyone, because the employees can log some overtime in the busy summer months.

The biggest labor-related challenge? Business management. The senior butcher now manages the plant, but he started with no management experience. Co-op board members have trained him along the way, even taking over some tasks – e.g. scheduling, critical to cash flow – when necessary. Accounting is largely handled by the IGFC treasurer and an outside accountant.

The board is all-volunteer, but because this business is critical to their livelihoods, they pay close attention. If the business expands again, they will consider hiring a general manager, but that isn’t yet necessary.

The current challenge is how to squeeze the available resources in the busy times when there’s so much demand – they now have to push pretty hard.

Financial sustainability plan

The business is self-sustaining and hasn’t needed outside funding since initial development and construction. Future expansions will be financed by members or possibly though bank loans.

Markets accessed

Most members sell their product through a variety of retail channels (e.g. off-farm, farmers markets, restaurants, grocery stores, farm stands). Only a few sell wholesale.

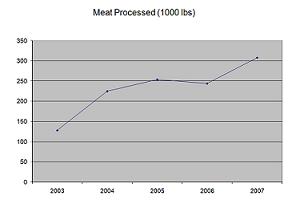

Growth to date

Business has grown steadily. IGFC now has 65 members, most of whom raise and sell fewer than 50 head of beef per year, though a few do 100-200 per year. The MPU processed more than 300,000 lbs of meat in 2007, with a retail value of $1,044,000. They have already done one expansion at the cut and wrap facility, which nearly doubled their hanging room capacity, but they are maxed out on space yet again. Due to these space and staffing constraints, the Co-op is limited in its ability to take on any new members at this time. They are working on how to increase throughput by expanding the current plant further or building their own, but the cost would be very high. To continue to grow or not? It’s a complicated question. It’s tempting to expand, but the Co-op is hesitant to overextend itself.

Greatest Challenges

When the unit first began operating, funds were very tight. It took at least two years until the Co-op’s finances stabilized. During that time, the Co-op tried to finance any additional needs through Co-op members instead of taking on debt from outside lending agencies. They now have a strong team in place, but finding and keeping the appropriate amount of skilled labor has consistently been a challenge. Looking ahead, the greatest challenge will be figuring out how and when to expand their operation in order to meet demand for their services.