Modular Harvest System

Hudson Valley, New York

“Now we are thinking of the MHS as a way for people to try out the business, get some experience operating under inspection, with FSIS. And it comes with a HACCP plan.” – Jess Hamilton

All MSUs have been conceived and built to add to local, inspected slaughter capacity. In New York, an MSU built to fill a commercial need is transitioning into a business incubator with potential reach beyond the original region and operator.

Background

The Glynwood Center, based in Cold Spring, NY, built a red meat “Modular Harvest System” (MHS) as a catalyst to provide farmers with “the necessary infrastructure for their farms to be environmentally sustainable and economically viable” (from Glynwood website). Glynwood, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving farming in NY’s Hudson Valley, convened a task force in 2008-2009 on challenges facing the region’s livestock farmers. The valley had numerous beef farms but little local sales, and producers said limited slaughter capacity was the problem. Glynwood decided to build an inspected mobile slaughter unit for the region.

They faced an immediate design challenge. All other USDA-inspected MSUs were allowed to slaughter and bleed livestock outside, bringing carcasses inside for skinning and cleaning. But the USDA Albany District Office would not allow slaughter outside in harsh winter conditions. After considering a design with a hydraulic ceiling, they found a 53’ long MSU, built for USDA inspection, for sale in California.

Innovative, Four-Module Design

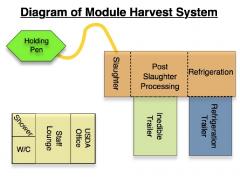

The completed MHS is the most complex “mobile” system so far, with four “modules”: a slaughter trailer, a refrigeration truck to chill and transport carcasses; an inedible parts trailer for offal, manure, and waste disposal; and an office trailer for MHS employees and the USDA inspector. It cost about $750,000, including project research, design, unit purchase and modification, transport, repairs, permitting, equipment, insurance, and other costs. The MHS was designed for use at docking stations that provide electricity, water, holding pens, and a chute that meets humane handling requirements.

(Diagram and photo courtesy of Glynwood Center)

Slaughter is done inside the trailer: the animal walks up a ramp into the squeeze chute inside the unit and is stunned with a captive bolt stunner, lowered to the floor, and hoisted for skinning. It is not comfortable for large animal slaughter and works best for sheep and small cattle. Hogs are also difficult: an insulated electric kill box would be safer, and without a dehairer they cannot provide skin-on carcasses, which some producers and their customers prefer.

Initial Operation

Glynwood created an affiliated non-profit organization, Local Infrastructure for Local Agriculture (LILA), to own the MHS and coordinate the project, including finding a partner to “field test” the MHS. The Eklund family, in Delaware County, had a diversified farm and the largest certified organic dairy in their part of New York, and they wanted to sell beef from their cull cows. They had been planning an on-farm processing plant and were willing to use the MHS until their own facility was built.

The Eklunds began operating the MHS under Federal inspection in April 2010. At several days per week, averaging four head per day, they were well under capacity and slowed further that winter. However, USDA was willing to send inspectors even once a month, because they inspected many other (non-slaughtering) processors in the area.

After slaughter, the Eklunds trucked quartered carcasses 90 minutes to a cut and wrap facility, then picked up finished product to deliver to customers. The system was inefficient and expensive, which limited the Eklunds’ use of the MHS. It also changed LILA’s perspective. The MHS was built to fill a perceived need for inspected slaughter, partnering with existing cut and wrap facilities. Yet when two separate businesses were involved, already slim profit margins vanished.

A New Approach

After ten months, the Eklunds stopped using the MHS to focus on building their on-farm plant, and LILA reevaluated its approach. First, they needed an integrated cut and wrap facility. They also realized the significant value of the hands-on, practical training in running a slaughter facility – challenges and all – that they had provided the Eklunds. The time with the MHS had reaffirmed the farmers’ intention to build their own plant. LILA realized that the MHS might have more value as a business incubator than as a commercial entity.

By early 2012, LILA had identified three potential partner sites in the Hudson Valley, the most promising in Columbia County. County officials have offered to use local agriculture development funds to build a docking site for the MHS. LILA wrote a starter business plan for a further processing facility and then found an entrepreneur to build and run it, as well as lease and operate the MHS, as one integrated slaughter and processing business. LILA is creating a pricing structure that won’t compromise their 501c3 status. Nonprofits can run businesses but may charge no more than 10 percent above cost. LILA is being careful to incorporate every cost into the business model so the system will be financially viable.

Finding Throughput

The most essential need is enough local demand for processing services to support that business. A Cornell University survey found enough stated demand from farmers to operate the MHS one day per week, which LILA estimates will keep the further processing business afloat. The responding farmers already market their meats and are fairly likely to follow through.

LILA is counting on a new relationship with the Northeast Livestock Processing Service Company (NELPSC) for more assured throughput. NELPSC was established in 2005 by the Hudson Mohawk Resource Conservation and Development Council, with support from the state’s agriculture department, to improve communication and coordination between farmers and processors in the region. NELPSC Coordinator Kathleen Harris, who has worked with dozens of farmers marketing meats in the region, will find enough farmers and livestock to keep the MHS and further processing plant steadily busy.

Moving Forward, Big Picture Goals

Jess Hamilton, LILA project coordinator, points to the evolution of their approach to the “local slaughter problem.” “Communities have approached us thinking the MHS can pull in and plug in and go. But it takes entrepreneurs, people who can go in and create the public-private partnerships.” The MHS, she says, must succeed in its next incarnation, so that LILA can confidently bring the system, business model, and related expertise to other communities. They will track not only costs and revenue at the new site but also data for a community economic multiplier calculation. “I don’t want to offer anything we haven’t proven.”

LILA’s broader community goals remain central: the MHS is not just a service provider but a social enterprise. They aim to work with entrepreneurs that are aware of social and environmental goals as well as the need to be profitable. “The bottom line,” Hamilton says, “is that bringing this business to a new area requires coordination and education of local government, entrepreneurs, livestock producers, and buyers. We hope to see positive financial, social, and environmental effects by bringing red meat processing and value added businesses back to town.”